As Turkey’s East Med isolation deepens, will Ankara seek maritime Syria deal?

Lebanon-Cyprus maritime agreements have further increased Turkey and Turkish Cypriots’ isolation in the Eastern Mediterranean amid growing Cypriot-Greek-Israeli alignment.

ANKARA — As a new Lebanon-Cyprus maritime deal deepens Turkey’s isolation in the Eastern Mediterranean, experts say Ankara has little choice but to turn to Syria as a counterweight for a potential future delimitation agreement.

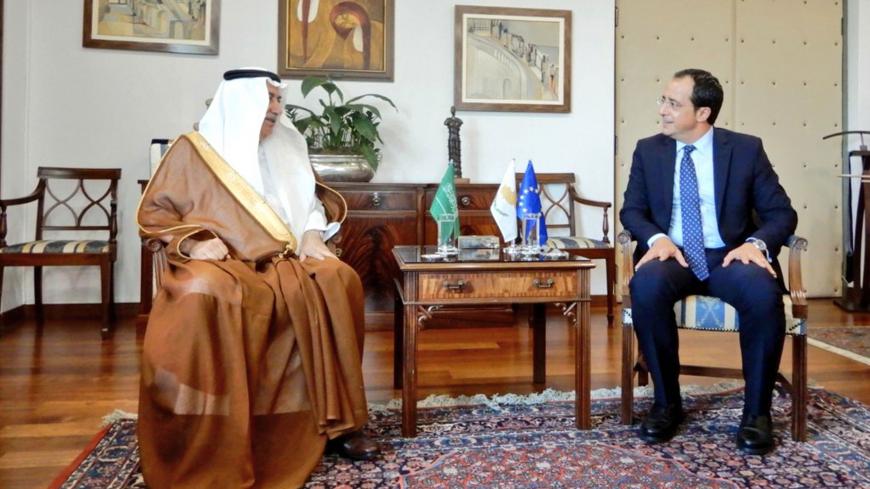

The maritime and exclusive economic zone delimitation agreements signed between Lebanon and the Republic of Cyprus on Nov. 26 not only advance bilateral cooperation between Nicosia and Beirut but also further isolate Turkey and Turkish Cypriots amid a growing Greece-Cyprus-Israel alignment.

Cyprus remains divided between the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, recognized only by Ankara, since Turkey’s 1974 military intervention following a Greek-backed coup that was aimed at uniting the island with Greece. Turkey, Greece and the United Kingdom continue to serve as guarantor powers under a complex security arrangement that was established when Cyprus gained independence in 1960.

The maritime deal is the Republic of Cyprus’ third such accord with regional neighbors, following agreements with Egypt in 2003 and Israel in 2010, despite Ankara’s long-standing objections that any unilateral delimitation by the Republic of Cyprus ignores the rights of Turkish Cypriots and therefore lacks international legitimacy.

“This agreement is completely illegal,” Omer Celik, spokesman for the ruling Justice and Development Party, told journalists on Dec. 9.

“It is an attempt to usurp the sovereign rights of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.”

Changing dynamics in the East Med

Celik also voiced Ankara’s unease over what it sees as expanding Israeli influence in Cyprus. “The Greek Cypriot administration is turning the Greek Cypriot region into a military outpost for certain countries,” he said, indirectly taking aim at Nicosia's growing military cooperation with Israel.

The Republic of Cyprus in September received a second batch of Israel’s Barak MX air-and-missile defense batteries, under a 2021 agreement with the Jewish state. Separately, Greece’s parliament on Dec. 5 approved the purchase of 36 Israeli-made long-range artillery rocket systems. The roughly $758 million deal is part of a broader push to modernize the Greek army’s posture in the Aegean, where territorial disputes with Turkey remain a flash point.

The increasing cooperation has unfolded in parallel with the steady deterioration of Turkish-Israeli relations. “For many years, Israel had a strong pro-Turkish stance,” Gallia Lindenstrauss of Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies told Al-Monitor, recalling the 1990s, when Ankara was one of Israel’s few regional partners.

According to Lindenstrauss, deteriorating Turkish-Israeli ties, along with increasing hydrocarbon discoveries in the region, were “a big push” for the trilateral cooperation between Israel, Cyprus and Greece.

The peak of that hydrocarbon discovery boom in the region in the mid-2010s coincided with one of Ankara’s loneliest chapters. Turkey’s support of the Muslim Brotherhood dislodged its relationships with Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, all of which viewed the movement as a national security threat.

At the same time, Turkey’s exploration activities in contested Eastern Mediterranean waters heightened tensions in its relations with Greece and several EU capitals.

In a bid to counterbalance its regional isolation, Ankara signed a maritime delimitation deal with Libya in 2019, a move strongly rejected by Greece, Egypt and the Greek Cypriots, who argued it encroached on their sovereign rights in the Eastern Mediterranean.

By late 2021, desperate to draw capital into a battered economy and unwilling to be shut out of emerging energy schemes, Ankara muted its support for the Brotherhood, halted its exploration activities and began stitching together a cautious reconciliation with regional rivals. The charm offensive extended to Israel as well. President Isaac Herzog’s 2022 visit marked the first high-level thaw in years, and the two countries restored full diplomatic relations later that same year.

Then came 2023, when the Israel-Hamas war blew apart the nascent Turkish-Israeli detente. Relations became openly hostile, with Ankara emerging as one of Israel’s fiercest critics, denouncing the Gaza campaign as genocide, a charge Israel strongly rejects, which sped up Israeli cooperation with Athens and Nicosia.

Shifting US priorities

Russia’s war in Ukraine, meanwhile, provided both Greece and Cyprus new room to maneuver as Washington reassessed its priorities and its partnerships. In 2022, the United States scrapped its decades-old arms embargo on Cyprus in a bid to pressure Nicosia to curb Russian capital located in Greek Cyprus — once widely used to bypass Western sanctions on Moscow amid the Ukraine war. This shift was made easier thanks to already frayed US-Turkey relations over disputes that included Ankara’s purchase of Russian S-400 systems.

“For some time now, the United States has been viewing Greece as both an important energy partner and, especially since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a key defense partner,” Gonul Tol, the director of the Turkey program at the Middle East Institute, told Al-Monitor.

Last month, energy ministers of Cyprus, Greece, Israel and the United States, held a summit in Washington. The parties “support the goal of diversifying the region’s energy supplies by reducing reliance on malign actors and improving connectivity between like-minded regional partners,” a statement from the US State Department said, taking a thinly veiled jab at Russia and Turkey by pointing out that Washington is positioning Israel, Cyprus and Greece as key partners in channeling Eastern Mediterranean hydrocarbon reserves to Europe.

“There seems to be a renewed push led by the US and Israel to improve regional energy infrastructure, which excludes Turkey,” Tol said. “A new and a difficult context is reemerging in the Eastern Mediterranean in Turkey.”

Is a Turkey-Syria maritime deal on the horizon?

As the regional balance tilts against it, Turkey is left with a shrinking set of options to counter the tightening triangle of Greece, Cyprus and Israel and topping options is a maritime deal with Syria. One option that stands out: a potential maritime-delimitation agreement with Syria, according to Gulru Gezer, a former diplomat now with Ankara-based think tank Foreign Policy Institute.

“A maritime exclusive economic zone deal with Syria would be suitable and significant,” she told Al-Monitor.

For Gezer, the logic is simple. The series of delimitation agreements between Cyprus and the other East Mediterranean countries are designed to edge Turkey and the Turkish Cyprus out of the emerging energy map in the hydrocarbon-rich region.

“Unless Ankara makes a countermove, more such agreements will follow,” she said. “The aim is to limit Turkey’s influence in the Eastern Mediterranean.”

An official Turkish source briefing Al-Monitor on the issue said there is currently no such work under way, but did not rule out the possibility in the future.

“Turkey is ready to address the delimitation of maritime jurisdictions with all relevant coastal states it recognizes, in a fair and equitable manner and in line with international law,” the source told Al-Monitor, explicitly excluding the Republic of Cyprus, which Ankara does not recognize.

“This position applies to Syria and other recognized relevant states,” the source added.

Earlier this year, Turkey’s transportation minister, Abdulkadir Uraloglu, suggested that Ankara intends to ink a maritime deal with Damascus. Greece and Cyprus immediately denounced the idea, arguing that Syria’s transitional government has no legal authority to sign international agreements. Al-Monitor reached out to the Syrian Foreign Ministry for comment.

“A deal of this kind with Syria would also serve Turkey’s interests,” Tol concurred. However, she added, “it is not realistic to expect Sharaa to be fully in Turkey’s corner.”

“We don’t know whether Syria will be willing to sign the kind of an agreement that Turkey wants Syria to sign.”