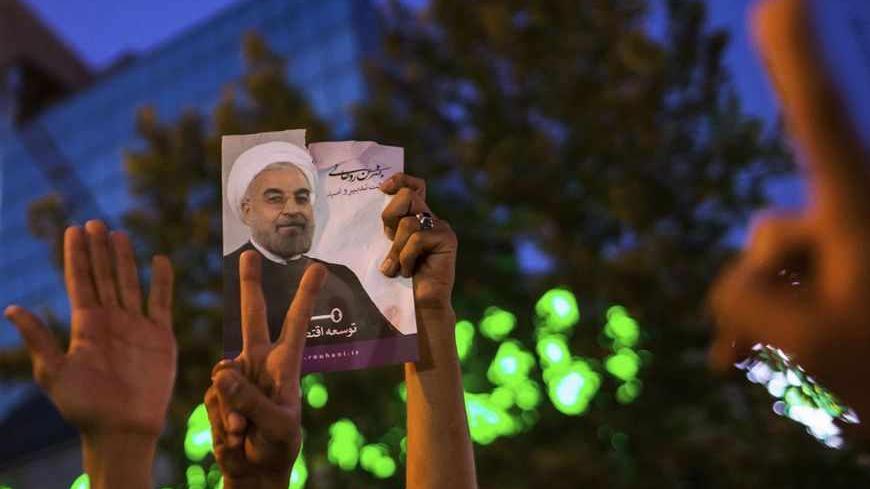

What Are Rouhani’s Critics Afraid of?

Subscribe for less than $9/month to access this story and all Al-Monitor reporting.

Or continue reading this article for free - Access 1 free article per month when you sign up.

By entering your email, you agree to receive ALM's daily newsletter and occasional marketing messages.