Culture

Fossil discovery repositions Morocco at center of human evolution 800,000 years ago

Once overlooked, Morocco has emerged as a focal point of human prehistory, with new discoveries and a landmark report reshaping what we know about our species’ evolution.

RABAT — A newly announced fossil discovery is further cementing Morocco’s central place in the prehistory of humanity. On Jan. 7, Moroccan and international researchers revealed the unearthing of ancient remains of hominins — human ancestors and close evolutionary relatives — in a cavity at the Thomas I quarry in Casablanca, shedding rare light on a pivotal and poorly understood phase of human evolution some 800,000 years ago.

Published in the journal Nature, the findings place North Africa at the center of debates over the divergence between early African human lineages and those that later gave rise in Europe and Asia to Neanderthals and Denisovans, respectively.

Researchers said the fossils, including lower jaw bones of adults and children, display a striking mix of archaic and more modern traits, reinforcing Africa’s long-established role in shaping human evolution. Attributed to 773,000 years ago, the dating of the remains is one of the most precise origins yet for a site yielding hominin fossils.

The discovery builds on a growing body of archaeological and paleoanthropological research that has transformed Morocco from a once-marginal player into a focal point of human evolutionary studies. In August, "A Reappraisal of the Middle to Later Stone Age Prehistory of Morocco" — a report by Nick Barton, Abdeljalil Bouzouggar, Stacy Carolin, and Louise Humphrey published in the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute — redirected attention to Morocco’s prehistoric record, calling for a "reappraisal" of its role in human evolution.

A guardian at the Thomas Quarry I archaeological site displays Acheulean stone tools in Casablanca, Morocco, July 29, 2021. (Photo: FADEL SENNA/AFP via Getty Images)

From the burial caves of Taforalt, in the east, to ancient ornaments from Bizmoune, in the southwest, recent findings are revealing that North Africa was not a fringe outpost of early humanity, but one of its cradles.

Tracing early humans

Among Morocco’s most revealing sites is Taforalt Cave, known locally as Pigeon Cave, in Berkane province. Excavations there have been underway since 2003, with the latest findings, published March 18, 2025, uncovering bones of the great bustard, a large bird now endangered in Morocco.

An unusually high concentration of great bustard remains was found clustered near human burials, suggesting that the birds held ritual or symbolic significance, rather than purely serving as food. Butchered remains and their placement beside graves point to funerary feasting traditions, revealing how humans in the region in the Middle to Late Stone Ages engaged in symbolic and social practices foreshadowing those in later, complex societies. The Middle Stone Age began roughly 300,000 years ago and ended 40,000 years ago, and the Late Stone Age started some 40,000 years ago and concluded almost 12,000 years ago.

Morocco is now "one of the core centers of human evolution in Africa," Nick Barton, professor emeritus at the University of Oxford and president of the British Institute of Libyan and North African Studies, told Al-Monitor. Before Barton and his team’s 25 years of research, he said, other regions, among them East Africa and Southern Africa, were "exclusively favored."

Taforalt and Bizmoune together offer what Moroccan archaeologist Abdeliljalil Bouzouggar, director of the National Institute of Archaeological Sciences and Heritage, in Rabat, described to Al-Monitor as "rare and rich information about the oldest human cultural behavior." Working alongside Barton and other international researchers, Bouzouggar has helped position Morocco at the forefront of studies in human evolution.

Bouzouggar calls Taforalt "one of the most important Paleolithic cemeteries in Africa." Excavations there have revealed "the oldest Pleistocene DNA in Africa, dated to 15,000 years ago," he said. The Pleistocene era began about 2.6 million years ago, according to the International Commission on Stratigraphy. "It is clear now that this part of Africa is telling a new story, and several discoveries, including the oldest use of personal ornaments, shed light on human evolution," Bouzouggar said.

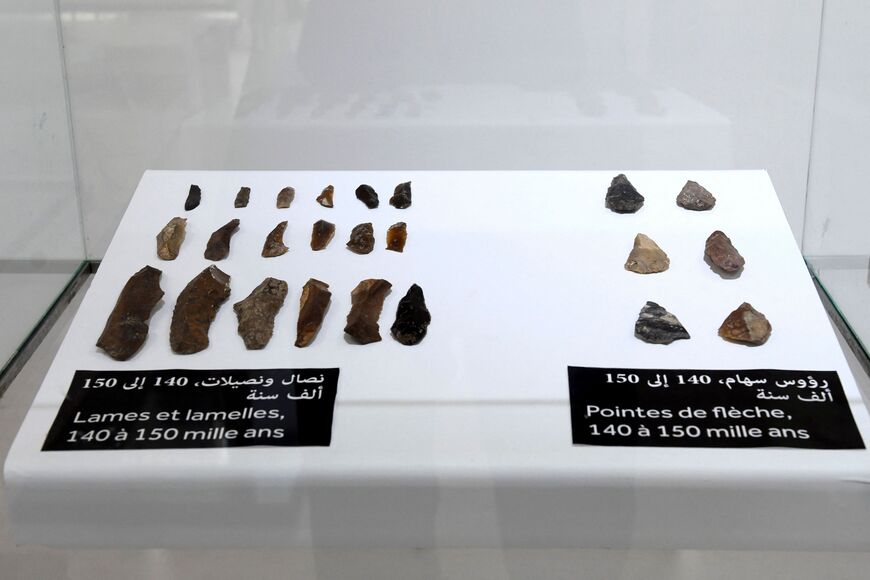

Artefacts unveiled by archaeologists in Morocco, who say they are among the oldest in the world, Nov. 18, 2021.

(Photo: AFP via Getty Images)

Life and ritual at Taforalt

At Taforalt Cave, layers of discovery are revealing how early humans lived, worked, and mourned their dead. Louise Humphrey, a researcher at the Centre for Human Evolution Research at London’s Natural History Museum, shared insights with Al-Monitor on what the findings in the Moroccan caves reveal about human behavior.

The deposits at several cave sites in the east, Humphrey said, show "an intensification in human activity around 15,000 years ago, which broadly coincides with a shift towards a more humid and warmer climate in this region."

She said the team’s excavations uncovered a diverse toolkit that included bone implements, basketry, grinding stones and evidence of systematic harvesting and processing of wild foods, such as sweet acorns, pine nuts, land snails and larger animals, like the Barbary sheep. The front of the cave appears to have been used for daily life, while "two alcoves at the back of the cave were set aside for funerary activity," Humphrey remarked.

Investigations in the alcoves revealed that the dead were buried alongside valued items, among them marine shells, ochre-stained grinding stones, horn-cores, ostrich eggshells and bird bones. At one burial site, Humphrey said, the team found "charred fragments of ephedra, which may have had a medicinal use." The treatment of the dead, she asserted, "reveals that the Later Stone Age people from Taforalt had a rich emotional and symbolic life."

World’s oldest beads

In the southwest, Bizmoune Cave has revealed one of the most extraordinary glimpses into early symbolic behavior. Nestled on the south-facing slopes of Jebel Hadid, about 9 miles northeast of Essaouira, the site yielded deposits dated to between 142,000 and 150,000 years ago. Among the discoveries were shell beads described by Bouzouggar, who led the excavation, as the world’s "oldest beads yet discovered."

Artefacts unveiled by archaeologists in Morocco, who say they are among the oldest in the world, Nov. 18, 2021.

(Photo: AFP via Getty Images)

The Bizmoune find underscores North Africa’s central role in the origins of symbolic behavior by humans, offering the earliest known evidence of shells fashioned into ornaments.

Excavations at Bizmoune also uncovered a lithic assemblage of stone tools and the waste from their production. Researchers identified the cutting tools as adzes and picks, notable for being made from the large cores of non-local metamorphic rock.

The assemblage also included flake-side scrapers, but the excavation team also noted no use of the Levallois technique, a hallmark of Middle Stone Age toolmaking. Similarly, the bladelet (small blade) tools typical of the Late Stone Age were not found.

Taken together, these elements place the Bizmoune finds in an "intermediate" phase between the Middle and Later Stone Ages. Evidence from Taforalt Cave supports this continuum, revealing that the gap between the two periods was narrower than previously believed.

Morocco back on the map

Barton said that he had felt compelled to uncover what lay beneath the surface in Morocco and described the thought process that triggered the extensive excavations to come. "Looking out from the southern tip of Gibraltar," he told Al-Monitor, "one is immediately struck by the narrow gap that divides Europe from the African continent."

If humans had once lived and moved across this corridor, he reasoned, "the Moroccan caves should share an equally rich archaeological record as the Gibraltar and southern Spanish caves."

In 1999, Barton reached out to Bouzouggar, who helped him lead cave surveys along the north coast of the Tingitana Peninsula. Their collaboration marked the beginning of the Morocco Caves Project—a decades-long effort that reshaped understanding of the region’s prehistoric past.

The work by Barton and his colleagues has, as he put it, "put Morocco back on the map in terms of the origins of modern Homo sapiens. For a long time, it had been largely discounted as an area of peripheral interest in terms of modern human evolutionary studies."