Ukraine war saps Russian sway over Caucasus, Central Asia

As the invasion of Ukraine drains Russia's forces, Moscow's grip on its former Soviet backyard in the Caucasus and Central Asia is loosening with unpredictable consequences, experts say.

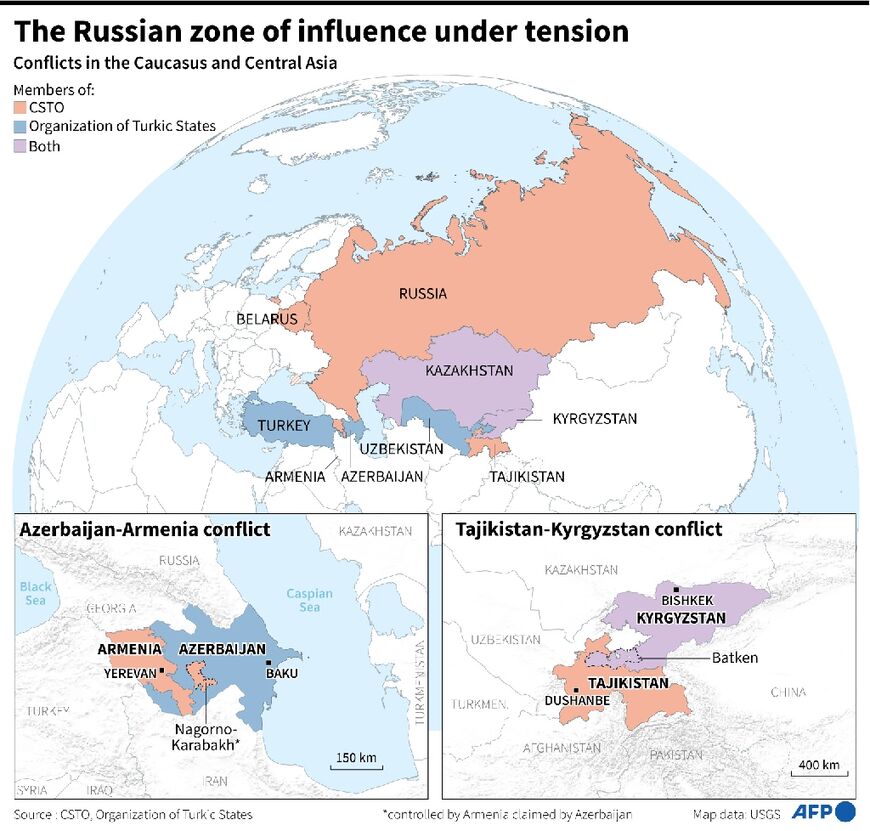

A recent flare-up of fighting between Armenia and Azerbaijan and deadly clashes between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have shown how surprisingly little sway Russia currently has over the region, which ranges from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea.

"The entire periphery of Russia is breaking up and it's obvious that it can't do anything to control it," said one European diplomatic source, asking not to be named.

A key illustration of Russia' rapid reputational loss in the region is the inaction of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a regional pact, in the face of the Azerbaijan-Armenia clashes.

Headquartered in Moscow, the CSTO groups Russia and the former Soviet republics of Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

- 'Failure to uphold' -

In Armenia, angry demonstrators have protested against CSTO's failure to assist their country against Azerbaijan, blaming a Russia they previously considered to be their ally.

"Russia's failure to uphold its treaty obligation to protect Armenia signals the beginning of a new era in the region, where smaller rivals like Azerbaijan can dictate terms with a confidence unthinkable only a year ago," wrote Ben Dubow at CEPA, a US think tank.

"The first half of September 2022 may well go down as the fatal moment Russia's lost its ability to dictate terms in its former empire," he said.

Waiting in the wings are China and Turkey, the other key actors in the explosive region, while voices sceptical towards Russia's Ukraine adventure are becoming louder.

At a meeting this month of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), a Moscow- and Beijing-led security group, China and India voiced criticism over the Ukraine invasion. Several central Asian countries have allowed pro-Ukraine demonstrations.

"The CSTO's weak response to the Azeri attacks is fueling protests among Armenians who want their country to leave the Russian-controlled military bloc," tweeted Moldavian researcher Denis Cenusa.

"We need to keep an eye on what's happening in Armenia," said Michael Levystone, an expert on Russia and central Asia at IFRI, a French international relations think tank.

Before Moscow's war against Kyiv, "there was a strong emphasis that Russia could not be defeated", said Murat Aslan at SETA, a Turkish research body.

But now, there is a chance of small-scale conflicts erupting, with Russia unable to influence the course of events.

"If Russia is defeated, everything will change," Aslan said.

On the other hand, should Russia emerge from Ukraine victorious after all, the "psychological effect" will mean that Moscow gets to "impose any agenda" in the Caucasus, he said.

- 'Root of the problem' -

But unless it does, faultlines will continue to become increasingly obvious.

One is a lack of recognised and demarcated geographical borders, which Moscow never thought were necessary. It treats the region as an administrative area rather than a group of genuinely independent countries.

"Almost half of the border between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan is still undefined, and that's the root of the problem," said Isabella Damiani, an expert on Central Asian geography at Versailles university in France.

Meanwhile Turkey, a historic ally of Azerbaijan and present in both the Caspian and Black Sea regions, stands to benefit from Russia's unusual inertia.

Like China, which is promoting its "new Silk Road" initiative, Turkey is quietly moving its pawns into place, notably via the Organisation of Turkic States (OTS) in which Ankara is they key player, said Levystone.

Turkey has concluded military partnerships with all Central Asian governments, including Tajikistan -- the only non-Turkic state in the region and whose language derives from Persian.

"There is the real question of whether OTS will turn into a political-military alliance around Ankara," Levystone said.

Aslan agreed, saying, "If Russian fails in Ukraine, that organisation will become much more active."